Since the brutal murder of George Floyd, much of the debate has focused on police brutality and reforming the police. Yet systemic prejudice still exists in the US. And there’s no getting away from it – every day in the US, an unarmed citizen killed by American police forces are disproportionately black.

As the Economist newspaper recently reported in its briefing on ‘Race in America’ (July 11-17, 2020): ‘That most brutal of injustices explains much of the power, the extent and the focus of the protests spurred by the killing of George Floyd, protests that have drawn a level of attention to race relations unseen since the 1970s.’

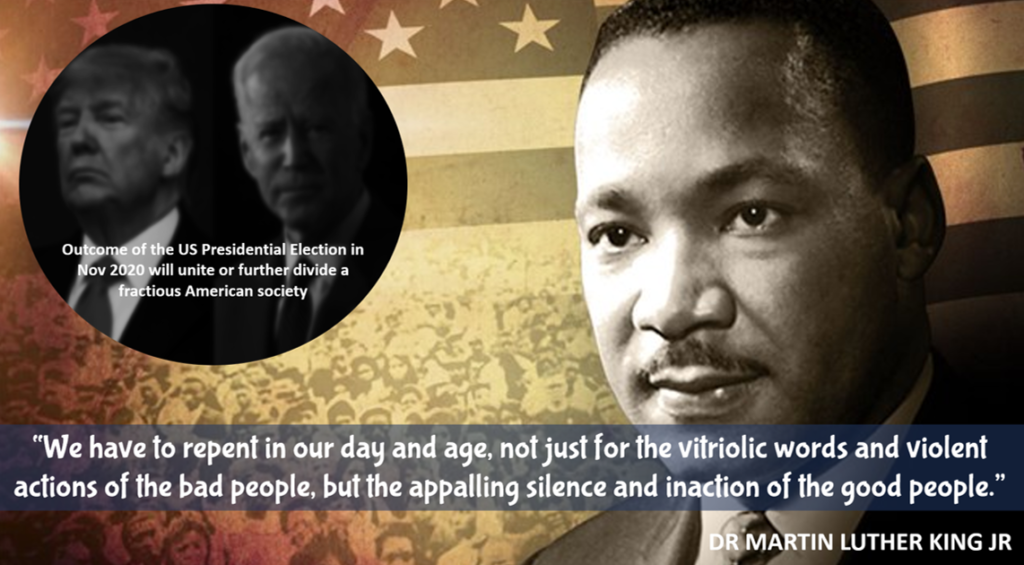

Clayborne Carson, a historian at Stamford University who edited Dr King’s letters and papers, makes the point that although ‘Whites Only’ signs and legal segregation is no longer visible in American society, there’s a lot of things that didn’t change and won’t change with only a focus on police brutality and reforming the police. Rather worryingly, Carson concludes that it won’t have any impact on the state of race relations in the US and in some ways is just the tip of the iceberg of injustices that Black Americans face on a daily basis. This will become a theme during the US Presidential Election in Nov 2020. Whether it can swing the vote for either candidate is uncertain.

“Unless people have the ability to basically change the opportunity structure, the changes aren’t going to be apparent,” observes Carson.

Tackling economic poverty and poverty of opportunity for Black Americans can’t continue to go unchecked. Research by Princeton University shows that between 1985-2000, just 6% of children from white families spent part of their childhood in neighbourhoods with at least 20% poverty rate. For black children, that figure was 66%. Fast forward to 2020 and the picture hasn’t really changed – just 4% of children from white families spend part of their childhood in neighbourhoods where the poverty rate is higher than 30%, compared with 36% of black children.

You don’t have to be a clinician to realise that poor neighbourhoods suffer from significant health and social consequences. For example, black families are 70% more likely to live in such neighbourhoods and their children are three times more likely to have high levels of lead in their blood. Research shows lead poisoning debilitates educational development and can lead to greater violence in adulthood.

Compared with white children, black children are nearly twice as likely to suffer from respiratory diseases such as asthma and five times more likely to die from it. Greater exposure to fine particulate material – the kind that most damages lungs – and lack of access to appropriate healthcare may go some way to explain why Covid-19 kills twice as many Black Americans as it does white Americans.

What perhaps is less well understood is that concentrated poverty is the hang-over from enforced segregation of Black Americans in the recent past.

In the mid-20th Century, millions of Black Americans were forced to live in Black neighbourhoods as a result of discriminatory laws and racial prejudice. In the 1970s, US cities were almost completely segregated in that 93% of Black residents would have needed to move to ensure complete integration.

So where does this leave American society today? As this blog explains, American society needs to correct persistent injustices against Black Americans.

Behaviour, policy, present-day racial discrimination that has resulted in the explosion of the frustration of not being heard and the subsequent BLM movement and the unfair initial conditions seeded by centuries of historical discrimination are tied together in a complicated knot of pathology.

Some of the tangled factors – systemic racism and family breakdowns – can lead to a superficial explanation for the continuity of inequality facing Black Americans and of course, can develop into a narrative of apportioning blame. But it’s not that simple, is it?

The US Presidental Election this November is an opportunity to tackle the inequalities that have so damaged American society and there’s now an urgent need for all communities, politicians and leaders to come together to find workable solutions to segregation, educational deficit and childhood poverty that has disproportionately affected Black Americans.

And as Dr Martin Luther King Jr eloquently put it: ‘We have to repent in our day and age, not just for the vitriolic words and violent actions of bad people, but the appalling silence and inaction of the good people.’

Recent Comments