This was the subject of discussion with Martin Hickley, a leading expert on all things cyber-crime and data protection related. Martin will be speaking at a special event that I’m chairing on 27 January 2015 at Cass Business School that will examine the impact of the EU General Data Protection Regulation on the financial services sector and what should be done in this current transition period ahead of the EU Regulation being activated across the European Union, possibly next year.

This was the subject of discussion with Martin Hickley, a leading expert on all things cyber-crime and data protection related. Martin will be speaking at a special event that I’m chairing on 27 January 2015 at Cass Business School that will examine the impact of the EU General Data Protection Regulation on the financial services sector and what should be done in this current transition period ahead of the EU Regulation being activated across the European Union, possibly next year.

Two words dominated the conversation with Martin: DATA BREACH.

This is a term that’s being used frequently in the media and elsewhere and indeed is referred in the current Data Protection Act 1998 as well as the forthcoming EU Regulation. However, what constitutes ‘data breach’ isn’t that clear or straight forward from a linguistic or legal perspective and interpreting this inaccurately could end up being a very costly mistake.

Under the proposed EU Regulation, a ‘data breach’ will need to be notified within 24 or 72 hours to the Supervisory Authority which in the UK is the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO).

There will then follow an investigation where further action against the organisation could be taken, depending on the scale and nature of the ‘data breach’.

If the recent crop of high profile cases within the financial services sector is anything to go by, then banks also the face the double whammy of punitive fines being awarded against them by the Financial Conduct Authority (FCA).

“A data breach is the unrecoverable loss or the organisation’s loss of control of some personal information that’s already in the public domain or can get into the public domain since the organisation no longer has control of it,” explains Martin Hickley.

Currently, the ICO views ‘missing data’ within an organisation as ‘lost data’. If you don’t know where data is, then you must assume that it’s about to go into the public domain, runs the argument. If you recover the data, it’s no longer in danger of being in the public domain and on this basis you’re no longer managing a ‘data breach’.

Under the Data Protection Act 1998, the decision about whether to report a data breach or not is up to senior management. The current guidance is that you should report it if you believe that there’s likelihood that someone else will notify the ICO. However, until senior management decide to report it, then it’s a ‘data incident’ under internal investigation and not a ‘data breach’.

A ‘data incident’ would therefore be any activity involving personal data within an organisation that its employees believe has by-passed existing processes or procedures for handling data, or any incident with respect to data they’re unsure about.

This does assume an organisation has formal data processes and procedures already in place, of course.

So what warrants an internal investigation? Take the following example: An email with attachments that contain personal sensitive information lands up in the wrong place.

So what warrants an internal investigation? Take the following example: An email with attachments that contain personal sensitive information lands up in the wrong place.

With email and their attachments – unlike printed material – once out there’s little or no possibility to recover the data and therefore such a breach, once detected, should be reported to the ICO.

With legal sanctions being applied by the ICO for ‘data breaches’ with personal information, organisations often focus on personal information and ignore the risks associated with other types of information they hold. And much of this stuff is commercially sensitive.

When the current Data Protection Act 1998 and guidance was written, organisations weren’t as hard-wired to the internet as they are today. The risk of leakages as well as the chances of being hacked has risen exponentially and so too the costs for ensuring that correct and adequate protection of all data is now in place.

According to Martin Hickley, organisations should refer internally to an ‘information breach’ rather than ‘data breach’ because any ICO investigation will trawl for a history of ‘data breaches’ recorded previously and questions will be raised if these incidents weren’t reported at that time.

There’s a strong possibility of appearing on Channel 4 News and being grilled by Jon Snow in such circumstances!

“Avoid using the term ‘breach’ alone because the ICO will automatically assume that it refers to a personal data breach. Some organisations have used the term ‘non personal data breach’ but that’s too cumbersome.

“For example in 2013, the FSA obtained several convictions for insider trading due to the leaking of price sensitive data from an employee of Cazenove Capital Management and part of the evidence consisted of emails sent to webmail drop boxes,” says Martin Hickley.

Under the EU Regulation, all data breaches will be required to be notified and the distinction between personal and non-personal data will have evaporated.

The cost of non-compliance of the forthcoming EU Regulation is horrendous, particularly for the financial services and pharmaceutical sectors.

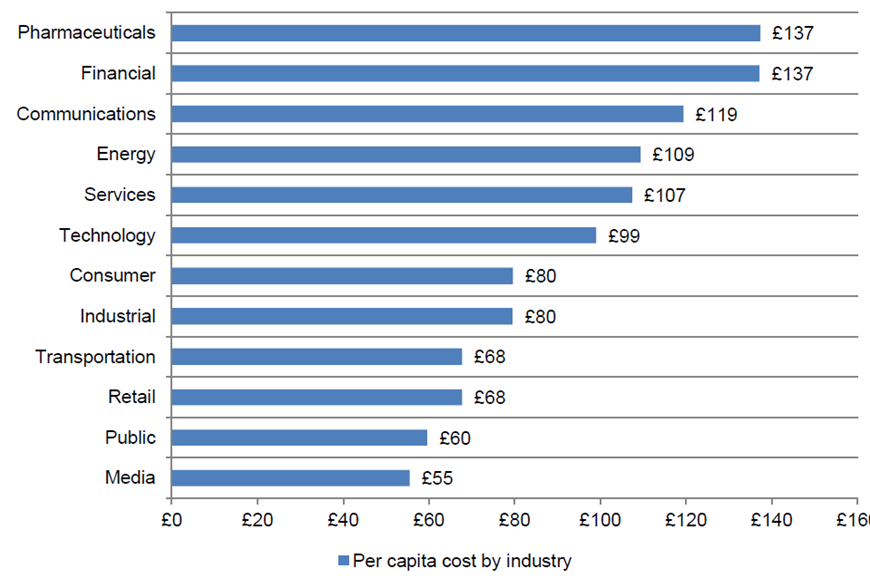

According to recent research conducted by the Ponemon Institute, the average cost for a data breach per record is GBP 137. If you multiply that my millions of records that are an unrecoverable loss, then that’s a sizeable financial risk to those companies operating in Europe.

The churn rate of customers, clients and patients also adds substantially to the risks faced by pharmaceutical companies (6.9%) and financial services (6.5%) and in order to significantly reduce the costs of a data breach, companies in these sectors should put a greater emphasis on customer retention and activities to preserve reputation and brand value.

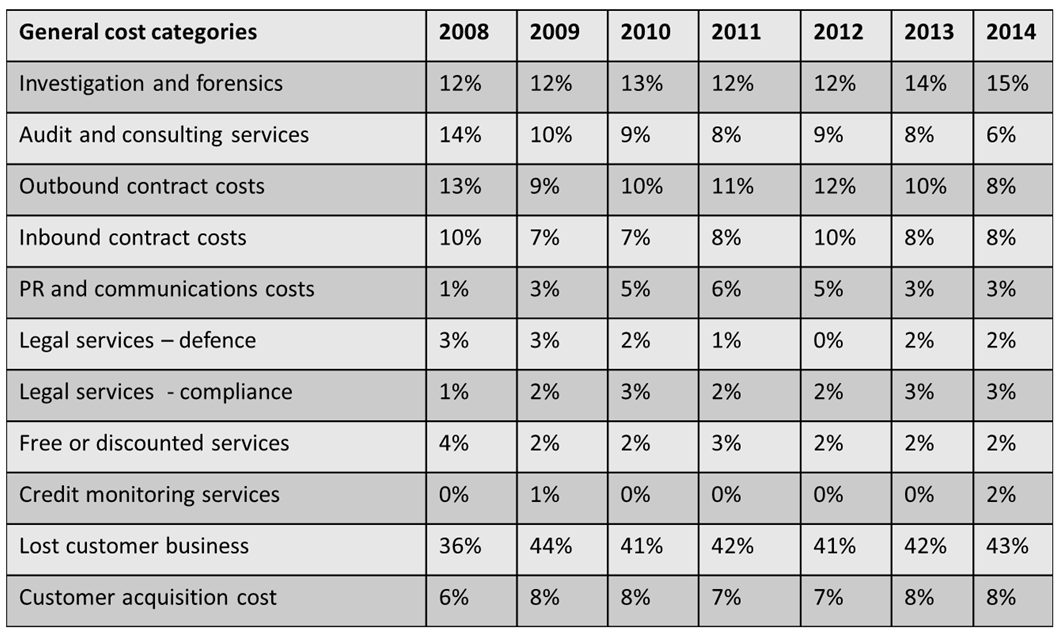

The costs to the business in terms of investigation, forensic and legal fees is tiny in comparison to the loss of customer and client business that has increased from 36% (2008) to 43% (2014).

In summary, existing regulatory guidance from the ICO is patchy at best and in this transition period organisations need to start to prepare for a much tougher and unforgiving regulatory regime under the forthcoming EU Regulation with the added jeopardy of increased media interest should things go wrong and there is a ‘data breach’.

Top five tips:

- Setup, define, and implement a breach process for personal and other information

- Do a risk based audit of information you hold and don’t confine it just to personal information

- Review electronic communication of data especially as attachments to emails and consider a data leakage product

- Ask suppliers of IT applications and infrastructure what’s their approach to ISO 270001

- Do a physical security review for how you hold data, both paper and electronic formats.

“Understanding these five areas will set a starting position or benchmark for your organisation. This will enable you to learn and monitor the situation; establish where your information is held electronically and physically; see how data is communicated and transferred; consider how email attachments can pose a security risk and learn from your suppliers as well as putting them on notice that you’ve become much more vigilant.

“And you can then start to put in place a robust governance, privacy and security strategy that will take a much longer view in order to safeguard business continuity in the future,” concludes Martin Hickley.

Recent Comments