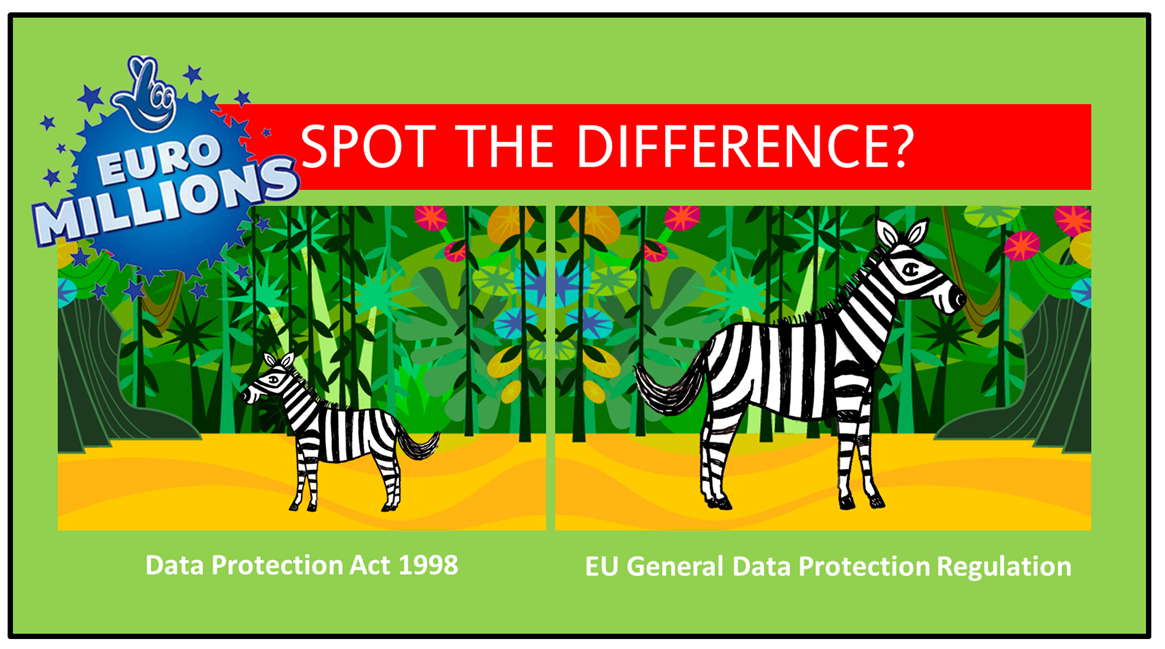

It’s not as easy as it looks, is it? And that goes for the differences between the Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998 and the forthcoming EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on course to gain consent from the European Commission, European Parliament and European Council of Ministers in early January2016.

It’s not as easy as it looks, is it? And that goes for the differences between the Data Protection Act (DPA) 1998 and the forthcoming EU General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR) on course to gain consent from the European Commission, European Parliament and European Council of Ministers in early January2016.

That means it will be fully implemented at the end of 2017 after the 2-year transition period expires.

Once GDPR has achieved agreement, the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC is repealed and the basis for the DPA 1998 has effectively been removed.

The legal position as to what happens during the transition period is still to be worked out but by far the safest course of action is for organisations to comply fully with the data protection principles enshrined under the GDPR, given that to do nothing will be deemed to be an aggravating factor in the light of a personal data breach or administrative sanction and will result in a higher financial penalty.

It’s a jungle out there when it comes to protecting personal data and privacy and there’s more than just a passing resemblance between the image on the left and the zebra on the right! And you’ve guessed right if you spot the main difference that GDPR is a much bigger beast. But the comparison between this and the previous DPA 1998 are much more than superficial.

Marketing consent

Under the DPA 1998, a negative opt-in had been relied on by marketers for gaining marketing consent (for example, tick here if you don’t wish to receive offers, etc).

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR, marketing consent must be explicit and in a form of:

- time limited opt-in

- in plain language (age appropriate to the Data Subject)

- with the requirement that the Data Subject is able to opt-out of profiling and object to the results of profiling.

Under the GDPR, the burden of proof to show consent has shifted to the Data Controller and the organisation will now need to prove consent wasn’t required due to legitimate processing conditions being met (in limited circumstances).

In all, there could be over seven separate types of consent an organisation needs to collect and hold, including consents for marketing, children, and use of sensitive personal data.

“If consent can’t be proved, a company could face an administrative fine under the GDPR and an Enforcement Order to stop processing customer data since consent is one of the conditions to be met to legally process data,” advises Martin Hickley, an expert in data protection, privacy and cyber security and Director of Data Protection at GO DPO® EU Compliance.

Sanctions

Under the DPA 1998, fines for breach of its eight data protection principles could be imposed, with a maximum £500,000 fine. A key condition was the personal data breach must have caused harm or financial loss to the Data Subject. Reporting to the Information Commissioner’s Office (ICO) of a personal data breach was voluntary.

Research shows that over the past four years the ICO imposed a paltry 65 fines on those organisations that had fallen below the acceptable standard for safeguarding personal data.

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR, organisations are subject to fines, Enforcement Orders and undertakings.

The GDPR creates two different types of financial jeopardy:

- fines for Personal Data Breaches (PDBs); and

- fines for Administrative breaches.

Both carry between 2-5% of previous year annual turnover for a commercial organisation subject to general EU competition law principles of fairness and proportionality.

The bar to show PDBs has been substantially lowered as Data Subjects now only need to show ‘distress’ rather than actual harm or financial loss, which is much lower evidential burden than under the previous data protection regime.

Furthermore, Data Controllers can be fined for around 28 Administrative breaches contained in the GDPR, making this the biggest financial jeopardy in terms of potential impact on business continuity.

The Supervisory Authority (the new name for Data Protection Authority) now has new powers to impose fines on Data Controllers and Data Processors for failing to observe the principles of the GDPR and the Supervisory Authority simply needs to show that administrative procedures haven’t been adhered to in order to punish the organisation.

“This poses a much greater risk to business continuity than even PDBs because these are far less difficult to prove,” explains Martin Hickley.

“For example, if you don’t collect consents properly, then the organisation can be slapped with an administrative fine if they are processing personal data without appropriate legal consent from Data Subjects,” adds Martin Hickley who advises all organisations to carry out a Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) in order to take remedial action straight away.

Notification and Legal Processing

Under the previous data protection regime, organisations were required to ‘register’ or ‘notify’ the ICO through an online questionnaire and then pay a fee, often called Notification in order to carry out data processing of personal data.

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR, prior notification of personal data processing by the Data Controller has been removed.

That’s the good news.

However, Data Controllers are now under a much more rigorous criteria –data processing can legally take place only after the organisation has assessed the impact of processing on the Data Subject, the security measures to protect such data and that the appropriate and up-to-date technical and organisational processes and procedures are all in place.

“This is an organisation-wide Data Protection Impact Assessment (DPIA) that documents how, what data, what consents, what processing and what type of security, i.e. how you comply with the GDPR. Similar or replicated processes can be covered by a joint DPIA. And every 2 years the organisation has to carry out an audit to prove its complying with its DPIA, called a Data Protection Compliance Review (DPCR).

“Failure to do so can result in an Administrative Fine of up to 2-5% of annual turnover and an Enforcement Notice to stop processing, which could effectively close down a business. As a result, the DPIA is a critical process for an organisation and it will have to share it with the Supervisory Authority if any investigation for failure to comply with the GDPR takes place.

Legal rights of Data Subjects

The biggest fundamental difference between DPA 1998 and the GDPR is the way each protects the personal data of Data Subjects.

Under the previous regime, the Data Subject had the right to request a copy of their data (Subject Access Request) on payment of a nominal fee. In addition, the Data Subject had a common law right of erasure or rectification of their personal data.

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR, these 3 rights are explicit and no longer require a fee. In addition, there is a right to have the Data Subject’s personal data extracted and sent to them in an electronic portable format that will allow them to switch between different providers, for examples, within banking and insurance services.

In addition there is a requirement to report a PDB within 24-72 hours to the data subject in order for them to take steps to protect their own personal data which they are legally obliged to do so.

Failure to do any of these under the GDPR carries an administrative Fine of 2% — 5% of previous year’s turnover.

Definitions of Personal Data

Under the DPA 1998 there are 3 main categories of data. Under common law, these have evolved and the categories of personal data expanded.

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR, the 3 main categories of personal data have been widened to include a much broader list of items that are regarded as being personal data. For example, the Internet of Things (IoT) and location data are formally included in the definition of personal data.

Failure to include these new personal data items in the DPIA can result in an Administrative Fine of 2%-5% of annual turnover.

Personal Data Breaches (PDB)

Under the DPA 1998, it is not mandatory to inform the Supervisory Authority if a Personal Data Breach occurs except under the Privacy and Electronic Communications (EC Directive) (Amendment) Regulations 2011 (PECR).

How this is different under GDPR?

Under the GDPR there is now a mandatory requirement to inform the Supervisory Authority within 24-72 hours of a PDB, and include references to the DPIA/DPCR conducted by the organisation.

Failure to inform the Supervisory Authority within the requisite time period required in order to report such an incident or failure to include the relevant information in such reporting of an incident can result in an Administrative Fine of 2%-5% of annual turnover.

Data Protection Officer (DPO)

Under the previous regime, some 38% of EU Member States made the appointment of a DPO compulsory where notification of a PDB wasn’t mandatory under the Data Protection Directive 95/46/EC.

How this is different under GDPR?

It is highly likely that the appointment of a DPO will be a mandatory requirement under the GDPR, subject to certain caveats, for example, they must not have any conflict of interest in carrying out the function. For smaller organisations, there is likely to be an exception where the duties and responsibilities of the DPO could be outsourced to a third party provider rather than having to appoint someone internally to do the job.

The new breed of DPO is an independent senior manager that reports to a Board director who has ultimate responsibility for data protection and privacy for the organisation. In some cases, that could be the CEO.

The DPO has oversight of all activities to comply with the GDPR. The person is charged with advising the organisation on all matters to the GDPR and the dialogue between the organisation and the Supervisory Authority.

“Even if the appointment of a DPO is not mandatory, the lack of a senior manager responsible for data protection and privacy will be a severe aggravating factor in PDB’s and Administrative Fines. In fact without a dedicated ‘DPO’ it’s likely that many organisations won’t comply with the GDPR because they’ll fall short of the requirement of a person to advise senior management on the GDPR, report PDB’s in the extremely short time-frame as well as conduct DPIA’s or DPCRs in an independent and correct way,” warns Martin Hickley.

Summary

These are just some of the differences between the DPA 1998 and GDPR and other major differences include how cross-border data transfers will be handled after the recent judgment that declared Safe Harbor was unlawful, the One-Stop Shop mechanism as well as the increased role of the European Data Protection Supervisor (EDPS) in overseeing independent Supervisory Authorities applying the new GDPR in a consistent way across the EU.

“If an organisation complies under the DPA 1998 it doesn’t follow that it will be also be compliant with the GDPR. The new regime moves the responsibility for showing consent to personal data processing onto the shoulders of the Data Controller and in this new regime the burden of proof has shifted. In reality, Data Controllers and Data Processors are guilty until proven innocent in the face of a complaint to a Supervisory Authority” concludes Martin Hickley.

Recent Comments